Walkthrough¶

Loading datasets¶

The core component of Podium is the podium.Dataset class, a shallow wrapper which contains instances of a machine learning dataset and the preprocessing pipeline for each data field.

Podium datasets come in three flavors:

Built-in datasets: Podium contains data load and download functionality for some commonly used datasets in separate classes. See how to load built-in datasets here: Built-in datasets.

Tabular datasets: Podium allows you to load datasets in standardized format through

podium.TabularDatasetandpodium.datasets.arrow.DiskBackedDatasetclasses. See how to load tabular datasets here: Loading your custom dataset.Regular tabular datasets are memory-backed, while the arrow version is disk-backed.

HuggingFace datasets: Podium wraps the popular 🤗 datasets library and allows you to convert every 🤗 dataset to a Podium dataset. See how to load 🤗 datasets here: Loading 🤗 datasets.

Built-in datasets¶

One built-in dataset available in Podium is the Stanford Sentiment Treebank. In order to load the dataset, it is enough to call the get_dataset_splits() method.

>>> from podium.datasets import SST

>>> sst_train, sst_dev, sst_test = SST.get_dataset_splits()

>>> sst_train.finalize_fields()

>>> print(sst_train)

SST({

size: 6920,

fields: [

Field({

name: 'text',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: False,

vocab: Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 16284})

}),

LabelField({

name: 'label',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: True,

vocab: Vocab({specials: (), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 2})

})

]

})

>>> print(sst_train[222]) # A short example

Example({

text: (None, ['A', 'slick', ',', 'engrossing', 'melodrama', '.']),

label: (None, 'positive')

})

Each built-in Podium dataset has a get_dataset_splits() method, which returns the train, test and validation splits of that dataset, if available.

Loading 🤗 datasets¶

The popular 🤗 datasets library implements a large number of NLP datasets. For simplicity, we have created a wrapper for 🤗 datasets, which allows you to map all of the 600+ datasets directly to your Podium pipeline.

Converting a dataset from 🤗 datasets into Podium requires some work from your side, although we have automated it as much as possible. We will first take a look at one example 🤗 dataset:

>>> import datasets

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> # Loading a huggingface dataset returns an instance of DatasetDict

>>> # which contains the dataset splits (usually: train, valid, test)

>>> imdb = datasets.load_dataset('imdb')

>>> print(imdb.keys())

dict_keys(['train', 'test', 'unsupervised'])

>>>

>>> # Each dataset has a set of features which need to be mapped

>>> # to Podium Fields.

>>> print(imdb['train'].features)

{'label': ClassLabel(num_classes=2, names=['neg', 'pos'], names_file=None, id=None),

'text': Value(dtype='string', id=None)}

As is the case with loading your custom dataset, features of 🤗 datasets need to be mapped to Podium Fields in order to direct the data flow for preprocessing.

Datasets from 🤗 need to either (1) be wrapped them in podium.datasets.hf.HFDatasetConverter, in which case they remain as pyarrow disk-backed datasets or (2) cast into a Podium podium.datasets.Dataset, making them concrete and loading them in memory. The latter operation can be memory intensive for some datasets. We will first take a look at using disk-backed 🤗 datasets.

>>> from podium.datasets.hf import HFDatasetConverter as HF

>>> # We create an adapter for huggingface dataset schema to podium Fields,

>>> # allowing you to use wrapped 🤗 datasets as Podium ones

>>> imdb_train, imdb_test, imdb_unsupervised = HF.from_dataset_dict(imdb).values()

>>> imdb_train.finalize_fields()

>>>

>>> print(imdb_train.field_dict())

{'label': LabelField({

name: 'label',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: True

}),

'text': Field({

name: 'text',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: False,

vocab: Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 280619})

})}

Note

Conversion from 🤗 dataset features to Fields is automatically inferred by default. This is a process which can be error prone. Nevertheless, it will work for basic use-cases.

In general, we recommend you set the fields argument of from_dataset_dict.

When we load a 🤗 dataset, we internally perform automatic Field type inference and create Fields. While we expect these Fields to work in most cases, we recommend you try constructing your own.

Once the Field s are constructed, we can use the dataset as if it was part of Podium:

>>> from podium import Iterator

>>> it = Iterator(imdb_train, batch_size=2)

>>>

>>> text, label = next(iter(it))

>>> print(text, label, sep="\n")

[[ 49 24 7 172 1671 156 22 11976 5 1757

3409 7124 202 ... 1]

[ 523 64 28 353 10 3 227 21 7 73941

52 28 186 ... 8668]]

[[0]

[0]]

Loading your custom dataset¶

We have covered loading built-in datasets. However, it is often the case that you want to work on a dataset that you either constructed or we have not yet implemented the loading function for. If that dataset is in a simple tabular format (one row = one instance), you can use podium.datasets.TabularDataset.

Let’s take an example of a natural language inference (NLI) dataset. In NLI, datasets have two input fields: the premise and the hypothesis and a single, multi-class label. The first two rows of such a dataset written in comma-separated-values (csv) format could look as follows:

premise,hypothesis,label

A man inspects the uniform of a figure in some East Asian country.,The man is sleeping,contradiction

For this dataset, we need to define three Fields. We also might want the fields for premise and hypothesis to share their Vocab.

>>> from podium import TabularDataset, Vocab, Field, LabelField

>>> shared_vocab = Vocab()

>>> fields = {'premise': Field('premise', numericalizer=shared_vocab),

... 'hypothesis':Field('hypothesis', numericalizer=shared_vocab),

... 'label': LabelField('label')}

>>>

>>> dataset = TabularDataset(dataset_path, format='csv', fields=fields)

>>> dataset.finalize_fields()

>>> print(dataset)

TabularDataset({

size: 1,

fields: [

Field({

name: 'premise',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: False,

vocab: Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 19})

}),

Field({

name: 'hypothesis',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: False,

vocab: Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 19})

}),

LabelField({

name: 'label',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: True,

vocab: Vocab({specials: (), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 1})

})

]

})

>>> print(shared_vocab.itos)

['<UNK>', '<PAD>', 'man', 'A', 'inspects', 'the', 'uniform', 'of', 'a', 'figure', 'in', 'some', 'East', 'Asian', 'country', '.', 'The', 'is', 'sleeping']

Our TabularDataset supports three keyword formats out-of-the-box:

csv: the comma-separated values format, which uses python’s

csv.readerto read comma delimited files. Pass additional arguments to the reader via thecsv_reader_paramsargument,tsv: the tab-separated values format, handled similarly to csv except that the delimiter is

"\t",json: the line-json format, where each line of the input file in in json format.

Since these formats are not exhaustive, we also support loading other custom line-dataset formats through using the line2example argument of TabularDataset.

The line2example function should accept a single line of the dataset file as its argument and output a sequence of input data which will be mapped to the Fields. An example definition of a function which splits a csv dataset line into its components is below:

>>> def custom_split(line):

... line_parts = line.strip().split(",")

... return line_parts

>>>

>>> dataset = TabularDataset(dataset_path, fields=fields, line2example=custom_split)

>>> print(dataset[0])

Example({

premise: (None, ['A', 'man', 'inspects', 'the', 'uniform', 'of', 'a', 'figure', 'in', 'some', 'East', 'Asian', 'country', '.']),

hypothesis: (None, ['The', 'man', 'is', 'sleeping']),

label: (None, 'contradiction')

})

Here, for simplicity, we (naively) assume that the content of the Field data will not contain commas.

Please note that the line which we pass to the line2example function will contain the newline symbol which you need to strip.

When the line2example argument is not None, the format argument will be ignored.

In addition to datasets in the standard tabular format, we also support loading datasets from pandas with podium.Dataset.from_pandas() or the CoNLL column-based data format podium.datasets.CoNLLUDataset.

The Vocabulary¶

We saw earlier that our dataset has two Fields: text and label. We will go into detail on what exactly Fields are later, but for now let’s just retrieve and print them out.

>>> text_field, label_field = sst_train.fields

>>> print(text_field, label_field, sep='\n')

Field({

name: 'text',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: False,

vocab: Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 16284})

})

LabelField({

name: 'label',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: True,

vocab: Vocab({specials: (), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 2})

})

Inside each of these two fields we can see a podium.Vocab class, used for numericalization (converting tokens to indices). A Vocab is defined by two maps: the string-to-index mapping podium.Vocab.stoi and the index-to-string mapping podium.Vocab.itos.

After loading all the datasets you wish to build your vocabularies on, you need to call the podium.Dataset.finalize_fields() method to signal that the vocabularies should be constructed.

Finalizing vocabularies¶

We will now briefly explain the reasoning behind the required boilerplate finalize_fields call and why it is important. The main reason is that manually calling this line gives users more control over which dataset splits, or datasets, are the vocabularies constructed.

For an example, we might want to either construct the vocabulary on all dataset splits:

>>> train, dev, test = SST.get_dataset_splits()

>>> train.finalize_fields(train, dev, test)

>>> print(train.field('text').vocab)

Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 19425})

We did this by passing any number of Datasets as the argument of finalize_fields, indicating the frequencies for the Vocabularies should be counted on all of those datasets. Once finalize_fields is called on a Dataset instance, the Dataset iterates over all of its Fields, updates frequency counts of their Vocab instances (if they are used) on all given datasets.

In case the argument is left as None (default), the vocabularies will only be built on the dataset on which finalize_fields is called:

>>> train, dev, test = SST.get_dataset_splits()

>>> train.finalize_fields()

>>> print(train.field('text').vocab)

Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 16284})

In this case, the Vocab was not built in the dev and test splits, preventing information leakage in some types of models. Another case where manual finalization of Fields is useful is Dataset concatenation. All in all, this line of boilerplate code allows a higher degree of control to the user.

Note

If your Dataset doesn’t use a Podium Vocab, you are not required to call finalize_fields.

Customizing Vocabs¶

We can customize Podium Vocabularies in one of two ways – by controlling their constructor parameters and by defining a Vocabulary manually. For the latter approach, the podium.Vocab class has two static constructors: podium.Vocab.from_itos() and podium.Vocab.from_stoi().

>>> from podium import Vocab

>>> custom_stoi = {'This':0, 'is':1, 'a':2, 'sample':3}

>>> vocab = Vocab.from_stoi(custom_stoi)

>>> print(vocab)

Vocab({specials: (), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 4})

This way, we can define a static dictionary which we might have obtained on another dataset to use for our current task. Similarly, it is possible to define a Vocab by a sequence of strings – an itos:

>>> from podium.vocab import UNK

>>> custom_itos = [UNK(), 'this', 'is', 'a', 'sample']

>>> vocab = Vocab.from_itos(custom_itos)

>>> print(vocab)

Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>',), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 5})

In this example we have also defined a Special token (Special tokens) to use in our vocabulary. Both of these static constructors are equivalent and can produce the same Vocab mapping.

We will now take a look at controlling Vocabs through their constructor parameters. In the previous code block we can see that the Vocab for the text field has a size of 16282. The Vocab by default includes all the tokens present in the dataset, whichever their frequency might be. There are two ways to control the size of your vocabulary:

Setting the minimum frequency (inclusive) for a token to be used in a Vocab: the

podium.Vocab.min_freqargumentSetting the maximum size of the Vocab: the

podium.Vocab.max_sizeargument

You might want to limit the size of your Vocab for larger datasets. To do so, define your own vocabulary as follows:

>>> from podium import Vocab

>>> small_vocabulary = Vocab(max_size=5000, min_freq=2)

In order to use this new Vocab with a dataset, we first need to get familiar with Fields.

Customizing the preprocessing pipeline with Fields¶

Data processing in Podium is wholly encapsulated in the flexible podium.Field class. Default Fields for the SST dataset are defined in the podium.datasets.SST.get_dataset_splits() method, but you can easily redefine and customize them. We will only scratch the surface of customizing Fields in this section.

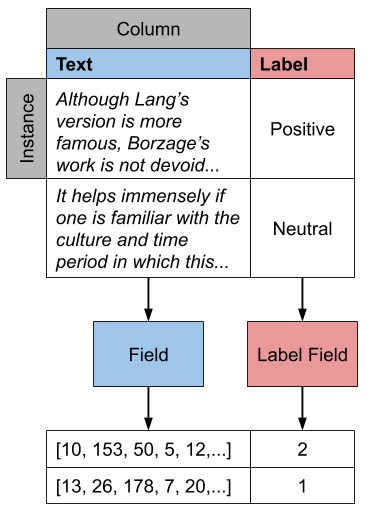

You can think of Fields as the path your data takes from the input to your model. In order for Fields to be able to process data, you need to which input data columns will pass through which Fields.

Looking at the image, your job is to define the color-coding between input data columns and Fields. If the columns in your dataset are named (as they are in the SST dataset), you should define this mapping as a dictionary where the keys are the names of the input data columns, while the values are Fields. The name of the Field affects only the attribute where the data for that Field will be stored, and not the input column! This is due to the fact that it more complex datasets, you might want to map a single input column to multiple Fields.

Fields have a number of constructor arguments, only some of which we will enumerate here:

name(str): The name under which the Field’s data will be stored in the dataset’s Examples.

tokenizer(str | callable | optional): The tokenizer for sequential data. You can pass a string to use a predefined tokenizer or pass a python callable which performs tokenization (e.g. a function or a class which implements__call__). For predefined tokenizers, you should follow thename-argsargument formatting convention. You can use'split'for thestr.splittokenizer (has no additional args) or'spacy-en_core_web_sm'for the spacy english tokenizer. If the data Field should not be tokenized, this argument should be None. Defaults to'split'.

numericalizer(Vocab | callable | optional): The method to convert tokens to indices. Traditionally, this argument should be a Vocab instance but users can define their own numericalization function and pass it as an argument. Custom numericalization can be used when you want to ensure that a certain token has a certain index for consistency with other work. IfNone, numericalization won’t be attempted.

fixed_length: (int, optional): Usually, text batches are padded to the maximum length of an instance in batch (default behavior). However, if you are using a fixed-size model (e.g. CNN without pooling) you can use this argument to force each instance of this Field to be offixed_length. Longer instances will be right-truncated, shorter instances will be padded.

The SST dataset has two textual data columns (fields): (1) the input text of the movie review and (2) the label. We need to define a Field for each of these.

>>> from podium import Field, LabelField

>>> text = Field(name='text', numericalizer=small_vocabulary)

>>> label = LabelField(name='label')

>>> print(text, label, sep='\n')

Field({

name: 'text',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: False,

vocab: Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: False, size: 0})

})

LabelField({

name: 'label',

keep_raw: False,

is_target: True,

vocab: Vocab({specials: (), eager: False, is_finalized: False, size: 0})

})

That’s it! We have defined our Fields. In order for them to be initialized, we need to show them a dataset. For built-in datasets, this is done behind the scenes in the get_dataset_splits method. We will elaborate how to do this yourself in Loading your custom dataset.

>>> fields = {'text': text, 'label': label}

>>> sst_train, sst_dev, sst_test = SST.get_dataset_splits(fields=fields)

>>> sst_train.finalize_fields()

>>> print(small_vocabulary)

Vocab({specials: ('<UNK>', '<PAD>'), eager: False, is_finalized: True, size: 5000})

Our new Vocab has been limited to the 5000 most frequent words. If your Vocab contains the unknown special token podium.vocab.UNK, the words not present in the vocabulary will be set to the value of the unknown token. The unknown token is one of the default special tokens in the Vocab, alongside the padding token podium.vocab.PAD. You can read more about these in Special tokens.

You might have noticed that we used a different type of Field: podium.LabelField for the label. LabelField is one of the predefined custom Field classes with sensible default constructor arguments for its concrete use-case. We’ll take a closer look at LabelFields in the following subsection.

LabelField¶

A common case in datasets is a data Field which contains a label, represented as a string (e.g. positive/negative, a news document category). For defining such a Field, you would need to set a number of its arguments which would lead to a lot of repetetive code.

For convenience, LabelField sets the required defaults for you, and all you need to define is its name. LabelFields always have a fixed_length of 1, are not tokenized and are by default set as the target for batching.

Iterating over datasets¶

Podium contains methods to iterate over data. Let’s take a look at podium.Iterator, the simplest data iterator. The default batch size of the iterator is 32 but we will reduce it for the sake of space.

>>> from podium import Iterator

>>> train_iter = Iterator(sst_train, batch_size=2, shuffle=False)

>>> batch = next(iter(train_iter))

>>> print(batch)

Batch({

text: [[ 14 1144 9 2955 8 27 4 2956 3752 10 149 62 5067 64

5 11 93 10 264 8 85 7 5068 72 3753 38 2048 2957

3 7565 3754 7566 49 778 7567 2 1]

[ 14 2958 2420 5069 6 62 14 3755 6 4 5070 64 5071 9

48 830 11 7 5072 6 639 68 37 2959 2049 7568 1058 730

10 7569 568 6 7570 5073 10 7571 2]],

label: [[0]

[0]]

})

There are a couple of things we need to unpack here. Firstly, our textual input data and class labels were converted to indices. This happened without our intervention – built-in datasets have a default preprocessing pipeline, which handles text tokenization and numericalization. Secondly, while iterating we obtained a Batch instance. A Batch is a special dictionary that also acts as a namedtuple by supporting tuple unpacking and attribute lookup.

Traditionally, when using a neural model, whether it is a RNN or a transformer variant, you require lengths of each instance in the dataset to create packed sequences or compute the attention mask, respectively.

>>> text = Field(name='text', numericalizer=Vocab(), include_lengths=True)

>>> label = LabelField(name='label')

>>> fields = {'text': text, 'label': label}

>>> sst_train, sst_dev, sst_test = SST.get_dataset_splits(fields=fields)

>>> sst_train.finalize_fields()

>>>

>>> train_iter = Iterator(sst_train, batch_size=2, shuffle=False)

>>> batch = next(iter(train_iter))

>>> text, lengths = batch.text

>>> print(text, lengths, sep='\n')

[[ 14 1144 9 2955 8 27 4 2956 3752 10 149 62 5067 64

5 11 93 10 264 8 85 7 5068 72 3753 38 2048 2957

3 7565 3754 7566 49 778 7567 2 1]

[ 14 2958 2420 5069 6 62 14 3755 6 4 5070 64 5071 9

48 830 11 7 5072 6 639 68 37 2959 2049 7568 1058 730

10 7569 568 6 7570 5073 10 7571 2]]

[36 37]

When setting the include_lengths=True for a Field, its batch component will be a tuple containing the numericalized batch and the lengths of each instance in the batch. When using recurrent cells, it is often the case we want to sort the instances within the batch according to length, e.g. in order for them to be used with torch.nn.utils.rnn.PackedSequence objects.

Since datasets can contain multiple input Fields, it is not trivial to determine which Field should be the key for the batch to be sorted. Thus, we delegate the key definition to the user, which can then be passed to the Iterator constructor via the sort_key parameter, as in the following example:

>>> def text_len_sort_key(example):

... # The argument is an instance of the Example class,

... # containing a tuple of raw and tokenized data under

... # the key for each Field.

... tokens = example["text"][1]

... return -len(tokens)

>>> train_iter = Iterator(sst_train, batch_size=2, shuffle=False, sort_key=text_len_sort_key)

>>> batch = next(iter(train_iter))

>>> text, lengths = batch.text

>>> print(text, lengths, sep="\n")

[[ 14 2958 2420 5069 6 62 14 3755 6 4 5070 64 5071 9

48 830 11 7 5072 6 639 68 37 2959 2049 7568 1058 730

10 7569 568 6 7570 5073 10 7571 2]

[ 14 1144 9 2955 8 27 4 2956 3752 10 149 62 5067 64

5 11 93 10 264 8 85 7 5068 72 3753 38 2048 2957

3 7565 3754 7566 49 778 7567 2 1]]

[37 36]

And here we can see, that even for our small, two-instance batch, the elements in the batch are now properly sorted according to length.

Loading pretrained word vectors¶

With most deep learning models, we want to use pre-trained word embeddings. In Podium, this process is very simple. If your field uses a vocabulary, it has already built an inventory of tokens for your dataset.

A number of predefined vectorizers are available (podium.vectorizers.GloVe and podium.vectorizers.NlplVectorizer), as well as a standardized loader podium.vectorizers.BasicVectorStorage for loading word2vec-style format of word embeddings from disk.

For example, we will use the GloVe vectors. The procedure to load these vectors has two steps:

Initialize the vector class, which sets all the required paths. The vectors are not yet loaded from disk as you usually don’t want to load the full file in memory.

Obtain vectors for a pre-defined list of words by calling

load_vocab. The argument can be aVocabobject (which is itself an iterable of strings), or any sequence of strings.

The output of the function call is a numpy matrix of word embeddings which you can then pass to your model to initialize the embedding matrix or to be used otherwise. The word embeddings are in the same order as the tokens in the Vocab.

>>> from podium.vectorizers import GloVe

>>> vocab = fields['text'].vocab

>>> glove = GloVe()

>>> embeddings = glove.load_vocab(vocab)

>>> print(f"For vocabulary of size: {len(vocab)} loaded embedding matrix of shape: {embeddings.shape}")

For vocabulary of size: 21701 loaded embedding matrix of shape: (21701, 300)

>>> # We can obtain vectors for a single word (given the word is loaded) like this:

>>> word = "sport"

>>> print(f"Vector for {word}: {glove.token_to_vector(word)}")

Vector for sport: [ 0.34566 0.15934 0.48444 -0.13693 0.18737 0.2678

-0.39159 0.4931 -0.76111 -1.4586 0.41475 0.55837

...

-0.050651 -0.041129 0.15092 0.22084 0.52252 -0.27224 ]

Using TF-IDF or count vectorization¶

In the case you wish to use a standard shallow model, Podium also supports TF-IDF or count vectorization. We’ll now briefly demonstrate how to obtain a TF-IDF matrix for your dataset. We will first load the SST dataset with a limited size Vocab in order to not blow up our RAM.

As we intend to use the whole dataset at once, we will also set disable_batch_matrix=True in the constructor for the text Field. This option will return our dataset as a list of numericalized instances during batching instead of a numpy matrix. The benefit here is that if returned as a numpy matrix, all of the instances have to be padded, using up a lot of memory.

>>> from podium.datasets import SST

>>> from podium import Vocab, Field, LabelField

>>> vocab = Vocab(max_size=5000)

>>> text = Field(name='text', numericalizer=vocab, disable_batch_matrix=True)

>>> label = LabelField(name='label')

>>> fields = {'text': text, 'label': label}

>>> sst_train, sst_dev, sst_test = SST.get_dataset_splits(fields=fields)

>>> sst_train.finalize_fields()

Since the Tf-Idf vectorizer needs information from the dataset to compute the inverse document frequency, we first need to fit it on the dataset.

>>> from podium.vectorizers.tfidf import TfIdfVectorizer

>>> tfidf_vectorizer = TfIdfVectorizer()

>>> tfidf_vectorizer.fit(dataset=sst_train, field=text)

Now our vectorizer has seen the dataset as well as the vocabulary and has all the required information to compute Tf-Idf value for each instance. As is standard in using shallow models, we want to convert all of the instances in a dataset to a Tf-Idf matrix which can then be used with a support vector machine (SVM) model.

>>> # Obtain the whole dataset as a batch

>>> dataset_batch = sst_train.batch()

>>> tfidf_batch = tfidf_vectorizer.transform(dataset_batch.text)

>>>

>>> print(type(tfidf_batch), tfidf_batch.shape)

<class 'scipy.sparse.csr.csr_matrix'> (6920, 4998)

>>> print(tfidf_batch[222])

(0, 2111) 0.617113703893198

(0, 549) 0.5208201737884445

(0, 499) 0.5116152860290002

(0, 19) 0.2515101839877878

(0, 1) 0.12681755258500052

(0, 0) 0.08262419651916046

The Tf-Idf counts are highly sparse since not all words from the vocabulary are present in every instance. To reduce the memory footprint of count-based numericalization, we store the values in a SciPy sparse matrix, which can be used in various scikit-learn models.